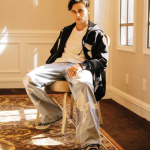

The collection of vintage RCA, Panasonic and Melodium microphones behind the Warehouse’s reception desk look like they were plucked from the vaults of Radio City Music Hall. The retro vibe is perfect for the occasion, as Michael Buble, the 31-year-old prince of crooner jazz, is at the Vancouver recording studio working on his latest album. For the interview I’d tried to lure Bublé out to the Irish Heather, a nearby pub that serves up Guinness pints you can stand a spoon in. Quaffing mid-afternoon beers, however, does not jibe well with cutting records, so I’ve come to meet him here, at the recording studio Bryan Adams built in the heart of Gastown.

Bublé grew up in Burnaby and is an internationally acclaimed pop singer of standard and not-so standard jazz tunes, a sort of Gen-X Tony Bennett. His butterscotch baritone has sold 10 million records worldwide and earned him five Juno awards and a 2006 Grammy nomination. When other teenagers were listening to Nirvana and Metallica, Bublé was listening to Harry Connick Jr. and Frank Sinatra. Even as a boy he was a fan of Dean Martin, Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby and the other greats favoured by his Grandpa Mitch, a plumber with a taste for vocal jazz.

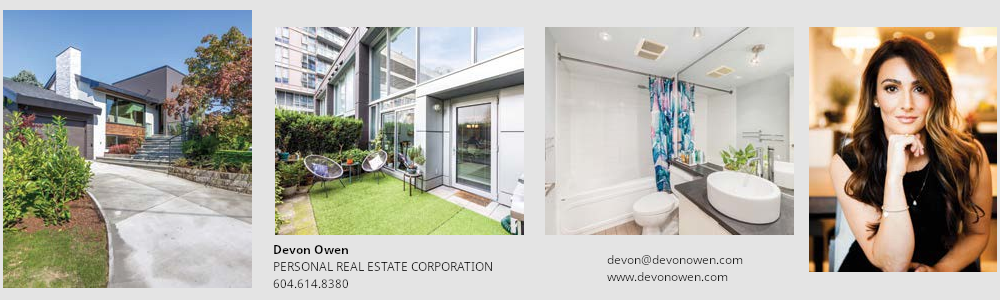

The big break for Bublé came in 2000, when he sang at Caroline Mulroney’s wedding and Brian Mulroney introduced him to Warner Brothers producer and record executive David Foster. Foster helped Bublé produce his breakout self-titled album a year later, featuring Van Morrison and George Michael covers in addition to such classics as “Sway” and “The Way You Look Tonight.” When Bublé comes to meet me and the Brian Jessel representatives who are delivering a loaner car—a white convertible 2006 BMW Z4 3.0si, to be exact, with red leather seats—he is cordial and relaxed, full of easy charm.

His mother and father join him on the street to check out his new ride, and as he mugs in the driver’s seat they are collectively wowed. Though Bublé is an international star, fame and wealth have yet to make him jaded. Wandering back into the studio’s courtyard, he takes a few practice putts on the rough green beside the parking lot. Then we sit down in the umbrella shade of a nearby patio table and crack open two chaste bottles of purified water.

Sponsored Ads

You’have unusual musical tastes for someone of our generation. Did you ever feel you were swimming upstream?

Honestly, I thought that I was right and everyone else was crazy. I didn’t understand how music that was so strong, with strong melodies and lyrics that were supported so well by them, couldn’t be understood by everyone, people of any age, any colour. I thought that, but then of course you’re failing for so many years you start to think, ‘Maybe I’m wrong.’ It took me not just having success, it took me having success in maybe 40 different countries, half of which didn’t speak English, to really realize how right I was.

You said “failing for so many years.” There’s that saying in show business that it takes five to seven years to become an overnight success. How long did it take you?

I was 16 when I started working in the clubs and other venues in Vancouver and Seattle. I didn’t get my big break until I was 25. And didn’t sell a record until I was 26. So that’s 10 years right there. And of course now it’s fine, I’m going to be 31 in a week. So we’re talking 14 years of working hard to make it happen.

How much of success was your own determination to make this work and how much was people helping you to get where you’re at?

This is not false modesty, but there are so many things, so many variables that go into a career like this. There were a whole bunch of people who believed, and a record company which put itself on the line to sign me, because at the time this music wasn’t exactly hip out in the market. And there are two things I truly believe that are instrumental in what’s happened to me. One is luck. I don’t care how good you are, you have to have a ridiculous amount of luck going your way.

You think so? Really?

Oh, yeah. There are people who are more talented than me who haven’t had their break yet, and there are people less talented who are huge, bigger than me. So it’s just a ridiculous amount of luck. And then the second thing was signing with the best manager in the music business. That padded my chances, which were small. But with Bruce Allen they got better.

There’s a lot of modesty on your part there.

Well, I’m being serious, I think I’m good at what I do, hopefully I’m one of the best in the world at what I do, but it doesn’t matter in this business.

It seems the relationship thing, who you know, is pretty potent.

Absolutely. And who you are as a person too. I mean, I look at the record company and these are my friends. I didn’t try to manipulate them. I just walked into their offices and I was who I was, a kid from Vancouver, and I was appreciative and, you know, nice. And they were nice, and appreciative. So neither of us mind working hard for each other.

Sponsored Ads

That’s one of the things I was wondering. Being nice, as many of us Canadians tend to be, I would think might work against you in the music business. But it seems to be working in your favour.

I don’t think I’m cutthroat and I don’t think I’m manipulative. You know my producer David Foster was very funny. He said it once. I said, “David, you know, I am manipulative.” And he said, “Michael, you’re not manipulative, you’re opportunistic.”

It’s definitely not the same thing.

Again, I think desperation is a huge factor. I’m still as scared of failing as I was after that first record came out on Warner Brothers, and it pushes me to succeed. If I come back from Africa or London and they say to me,

the second I get back, “Look, we’ve got a big television show for you to do,” every single time the people I have around me, and me, we just say, “Let’s go. Let’s go!” And David Foster always says it, and Bruce Allen says it too: “You can sleep when you’re dead.” There are so many factors. It’s luck and it’s hard work.

You have a great sense of humour. Does humour help?

No, you know what, I think humour helped in front of people, but in my own private time I cried, sometimes. I mean, it was horrible. You know, it’s tough, it’s tough to never know. It’s not like a lot of other businesses where you go, you know, if I really do work hard, if I really put in the time, and I’m really good, something— something will happen. It will click. I will get the job, I will get the promotion. Here it’s just—there’s no guarantee. So it’s scary.

Do you feel that every time you do an album, you’re sort of on the edge, on the precipice?

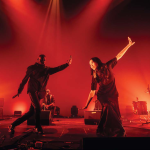

Absolutely. Absolutely. I think you shouldn’t lose that. I’ve lost it on stage. I’ve lost that feeling on stage, live. I have no nerves up there

That’s great in a way. Then you can just sink in.

I love it. I love every second of it up there. That’s where my sense of humour has come in and that’s what’s given me an edge: the show is a show, it’s not a concert. Because I’m so tired of going to concerts where I sit there for two hours and all they’ve done is played their music. I mean, I could have sat home and bought the CD, had a glass of wine. I wouldn’t have had to line up to go to the bathroom, you know?

I used to say to myself, God you know, if I had a couple million bucks and a house and I was secure, then I can just have fun and do the music I want to do. But you know what, it’s not true. I’ve got the money, Bruce Allen made me more than I can ever spend now. And it doesn’t matter at all, it has nothing to do with it. Really, it’s even more about the artistic side of it, the integrity, than it ever was before. It’s almost like now I feel I can’t afford not to really focus, to really give it, you know—to really give it.

How do you like being in Vancouver?

I’ll never leave. I’m telling you, man, I’ve been to 41 countries this year. There’s only one other place that even comes close, and that’s Melbourne, Australia. It has the vibe of Vancouver, the people. [I love] our energy, how cool and laidback everybody is. Toronto is like New York. Here’s it’s L.A.— we have two-hour lunches. This is the greatest city in the world.

What car did you learn to drive on?

A 1984 Pontiac LE 6000. I’ve never had anything fancy. This Brian Jessel BMW Z4 is by far the fanciest car I’ve ever had in my life.