Canada is truly a multi-cultural nation. Though so many of us come from different places, in Canada we come together with a collective pride of place. It’s this feeling, this energy that continues to attract people, professionals and families. They want to be a part of Canada.

My own family is a good example. Born in Hong Kong, my parents took an international approach early on, sending me to high school in the U.S. when I was only 15 years old. This decision was made in order to keep my opportunities open, and we all thought it was a great decision.

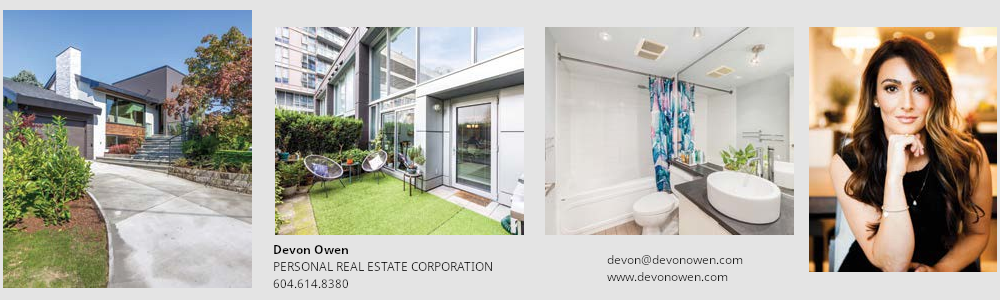

Sponsored Ads

A few years after this, my father resolved to leave the country. It was the mid-80s to early 90s, and many worried people were leaving Hong Kong preemptively – they feared the government would change so dramatically that we would lose our freedom once China regained possession of Hong Kong in 1997. Given that we’d traveled previously to Vancouver after visiting the U.S. west coast, Canada was on top of my father’s list of possible new homes. This was an extremely exciting move for the family in 1988. A historical note: as it turns out, in the past decade Hong Kong has seen a resurgence in

population after all that fear over the then menacing ‘red China’ influence, not much changed after all and so many natives have since returned home. Today, the new wave of immigrants is coming from Mainland China – the 2009 Census shows 9,375 new immigrants from the Mainland and only 319 from Hong Kong. As one of the current leading nations of the world, China has changed dramatically in the last decade. The communist government has slowly opened up, encouraging new- business start ups and the export of goods.

The economy is robust and we are strongly respected from within the country and by our peers. But even with all of that, there are some of China’s 1.3 billion+ citizens who long to live in less crowded cities than the major Chinese centers. Many of them have chosen Canada, and more specifically Vancouver as an ideal landing city. In Vancouver, immigrants have found a familiar home ample Chinese restaurants, newspapers, TV and radio stations, and retail specialists, from car dealerships to department stores, to assist them in every way. With so many immigrants still learning English, they have all the conveniences of home in this multi-cultural city.

As a resident for 23 years, I can say this: living in Vancouver is wonderful. From winter to summer, the climate is always mild and moderate. We have the sea, the mountains, scenic highways and true multi-cultural spirit – all of which makes this city ideal for relocating Chinese. Not to mention that it’s geographically well positioned to make it easier and faster to return to China for visits.

When we initially moved here, my family lived in a recently developed area in Richmond – all newly built homes. It was the first time I had a lawn to take care of. With the majority of people living in Hong Kong’s towering apartment buildings, this luxurious patch of grass was unheard of. My sister and I were thrilled, rambling through the rooms in our 3,000+ sq. ft. house, the memory of our 1,300 sq. ft. apartment distant and not so fond. It was truly a life changing experience.

But all these joys and advantages don’t completely cancel out the challenges of assimilating to a new country and way of life. I remember my family’s first Christmas in Canada in 1988. Coming from crowded Hong Kong, where businesses stay open late, on weekends and even on holidays like Christmas and New Year, we were practically stranded – no place to eat since all the restaurants were closed, and no where to shop, since the grocery stores and malls had also shut down. We did end up finding a Chinese restaurant that was open, but of course it was packed with hungry customers and long lineups. In contrast to the busy-ness that surrounded us in Hong Kong, this

Sponsored Ads

“Many of my own immigrant customers tell me that they’re purchasing a BMW because they so enjoy driving in Van”

peacefulness was jarring. Today I still chuckle to myself when Chinese customers come in late, just as we’re closing – with Asian merchants closing up shop in the evening, some of them as late as 11 pm, they’re used to having a good five more hours to do their business. Whenever a newly landed Chinese customer arrives at our dealership, they will usually ask for a “Top Model” X5.

By that, they mean all options inclusive, which is how BMWs are sold in China. The difference in Canada is that we start with a base price, then add options on top and – buying an X5, for example, can involve $20,000 worth of added options. There have been so many times where I have had to explain in detail what different packages include – Chinese customers are always confused why we would do it this way. In China, cars come fully loaded in perhaps two styles – Premium X5 (one with average options) and Ultra Luxury X5 (to designate a car loaded with almost every single option).

It is also typical for customers in China to be able see the car they’re buying – they aren’t used to factory orders and find it important to see the car they’re buying before they make their purchase. Plus they almost always pay cash outright – leasing is just not done. It’s a bit of a learning curve for immigrants, the way we sell cars here.

It’s all about managing their expectations – teaching them to trustthatthe car and the options they order will be delivered exactly as they have specified and educating them on how smart it is financiallyto reinvest in a new car through leasing every two to three years. Our first car in Canada was a 1988 Red BMW 325i. With its ellipsoid headlights, it was truly technologically advanced in those days. Since the prices were so good compared to those in Hong Kong, in six months, my father quickly traded it in for a 735i for my mother’s birthday – an excellent deal at the time.

Here you can find your ideal BMW at about half the cost of what you would pay in China. Take the X5 35i, for example. It’s one of the most popular models bought by Chinese immigrants, at an average cost of $80,000 to $85,000 (including HST) – by contrast, the equivalent in China costs a hefty $130,000. It’s no wonder new immigrants rush out to purchase luxury cars like BMWs. Many of my own immigrant customers tell me that they’re purchasing a BMW because they so enjoy driving in Vancouver.

This is an amusing turnaround because in China, most people with money wouldn’t be bothered to drive themselves around – they opt for a chauffeur to avoid the choking traffic congestion in major cities. But here, BMW is the Chinese immigrant’s vehicle of choice. Speaking of traffic, last July when I returned to Shanghai for the Expo, I was riding in a taxi, fearing forthe pedestrians and cyclists who attempted to share the road with the cars. In Canada, drivers will slow and stop courteously.

And then there were the long lineups in the hot sun. I watched as people brazenly cut into line, shamelessly angling for a better spot. Most Canadians are much too polite for this kind of behaviour, but I still occasionally observe, with a little embarrassment for my people, new immigrants trying to get away with avoiding lineups here.

As a Chinese immigrant who has been lucky enough to have traveled around the world and lived in a few international cities, I feel privileged to have the point of view that I do have – I understand the locals’ approach to immigrants, as well as the new immigrants challenges. The one thing we all share: pride in our wonderful home and native land. We are truly lucky