At last! BMW has its own Formula One team on the grid. Some years ago, a then-head of BMW Motorsport told me that despite all the successes his company had enjoyed in Formula One as an engine supplier, his greatest dream was that BMW would compete in the big series as a constructor with complete control, not as a “contractor.”

Sponsored Ads

At last! BMW has its own Formula One team on the grid. Some years ago, a then-head of BMW Motorsport told me that despite all the successes his company had enjoyed in Formula One as an engine supplier, his greatest dream was that BMW would compete in the big series as a constructor with complete control, not as a “contractor. ”With the 2006 F1 season, that dream has finally become reality and BMW builds the car from stem to stern, from powerplant to nose cone.

And for what is basically a new entry in the series, BMW isn’t doing too badly at all with several points-scoring drives and the promise of better things not too far down the road. BMW’s racing history goes back many decades, of course, though few people realize the varied branches of motorsport in which the famed Bavarian automaker has enjoyed success.

Flashes of BMW motorsport history include F1 World Championships with Brabham, victories at Le Mans and many successes in various touring car championship series and rallies around the world. There aren’t too many branches of motorsport BMW hasn’t been involved in over the years and involved as a winner. BMW’s early forays into open-wheel racing (as opposed to sports cars and touring car racers) included nearly 10 years as an engine supplier for the old Formula Two series. From the early 1970s to the early 1980s, BMW was the benchmark in this class of racing, intended as a stepping-stone to Formula One.

Drivers with BMW engines in this series who later became F1 stars included Jean-Pierre Jarier, Patrick Depailler, Jacques Laffite and other big names. BMW first took a run at F1 in 1980, announcing a partnership with Brabham as an engine supplier. Brabham BMWs were very competitive machines, and when the first Grand Prix of 1982 got under way in South Africa, the team’s two drivers, Nelson Piquet and Riccardo Patrese, were on the front row of the grid.

The first win for Brabham BMW and the remarkable 4-cylinder, turbo charged engine came in Montreal the same year when Piquet took the checkered flag. In 1983, Piquet won the World Championship in his BMW, an amazingly rapid path to the pinnacle of auto racing since it was just 630 days since the engine first appeared in an F1 event. At the end of 1987, BMW withdrew from F1 after many victories when the engine formula was changed and turbo power plants “outlawed.”

It was the end of one of the most exciting eras F1 had ever seen. BMW re-entered F1 in 2000, partnered with the famed Williams team. This time around the engine of choice was a V-10 and, as always, BMW designed and built a very competitive power plant. In fact, BMW Williams driver Ralph Schumacher took third place in the new team’s very first event — the Australian Grand Prix in March of 2000. It was the most successful debut for an F1 engine builder since 1967.

In 2001 the team posted four wins with drivers Ralph Schumacher and Juan Pablo Montoya. Between them, the duo had nine podium finishes. The third year saw the team runner-up in the Constructor’s Championship, only giving best to the over whelming superiority of Ferrari. In the years following, BMW drivers took many a trip to the podium, but by the 2005 season the company began to believe that the time was approaching when the old dream of completely controlling a team should be fulfilled. 2005 was a difficult season, though there were highlights.

After six seasons with Frank Williams and 10 wins, 45 podium finishes and 17 pole positions, BMW decided to “go it alone” and began the transformation by taking over the Swiss Sauber team. Peter Sauber, himself something of a motorsport legend, remains as an advisor, but the team is 100 per cent BMW, despite the name “BMW-Sauber” under which the cars are entered this season. The new BMW team is especially interesting to Canadians because one of its drivers is the great Jacques Villeneuve, who is teamed with Germany’s Nick Heidfeld and test driver Robert Kubica of Poland. We tend to take Villeneuve very much for granted in this country, allowing several seasons with a more or less uncompetitive team to cloud our hopes for the future. After a brilliant career in lesser formulae, Villeneuve took the world of CART Champ Cars by storm, winning both the championship and the famed Indy 500 in 1995.

His move to F1 was no less sensational, putting his Williams on the pole in his very first Grand Prix. He tallied a series of winning drives and at the end of his second season he was F1 World Champion. Nick Heidfeld is a driver who still hasn’t fulfilled his promised potential. Early in his career, he was being talked about in the same terms with which later F1 pundits were discussing Fernando Alonso and Kimi Raikonen: as a young driver with “World Championship” written all over him.

Luck hasn’t been on Heidfeld’s side, but he has seen his share of podium finishes and a pole position, not to mention flashes of undoubted brilliance in many races. He’s only just turned 29, so 2006 could still be his breakthrough year. Incidentally, both Villeneuve and Heidfeld live in Switzerland. Robert Kubica is the team’s test and substitute driver and the one who drives one of the BMWs in F1’s Friday practice sessions prior to race weekends.

If either Villeneuve or Heidfeld is injured or falls sick, Kubica will step into a car come race day. The team is convinced that Kubica can make the leap into F1 in time and while he waits in the wings, he completes the many exhaustive test sessions F1 teams must involve themselves in between races. Only 21 years old and a proven winner, Kubica has lots of time to break into the big series and in the meantime he has great opportunities to become thoroughly familiar with the handling and performance of an F1 car.

And just what kind of car has the new BMW team and its several hundred employees put together? There’s no doubt that it’s competitive, but in the intensively fought field of F1, a lot of good cars and competent drivers never make it into the points. BMW has made it clear that it has made a long-term commitment to F1 and is not expecting miracles right out of the gate. Even so, there’s every sign that wins may not be too far down the road. In the entire world of auto racing, there’s nothing as complex and technically sophisticated as an F1 car.

Cars from rival series may have their appeal and many of them come close to F1 in some areas of technology, but as a package, an F1 car is clearly the high tech benchmark. They involve some of the most expensive materials known outside the U.S. Space Program, are put together by the most skillful and proficient engineers in the auto industry and incorporate electronics to baffle the most earnest computer buff. Unsurprisingly, they are the most expensive race cars anywhere — and sometimes by several million dollars per car.

The BMW entry this season was developed from scratch, although some Sauber know-how was influential in its development. It’s every millimetre a new design, according to BMW. Many components are fabricated from carbon fibre – widely used in building race cars and even found in some road cars these days. In F1, aerodynamics is a critical area and has been for decades now. Every element of the car is subjected to wind tunnel tests to make sure that downforce the pressures that keep the racecar “glued to the road” is maximized.

Also, the basic body of the car, called the “tub” in F1 parlance, must be designed as a crashproof structure to help the driver survive even in a serious shunt. Many a driver has walked away from a nasty crash that may even have involved losing all the wheels and having the engine torn from the tub, thanks to the ruggedness of the “cell” in which he, or perhaps she, sits. And what looks like a fairly simple steering wheel is actually a control center for a bewildering maze of electronic performance and safety systems.

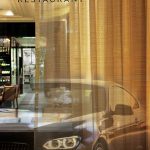

On one visit to a BMW F1 pit, a mechanic told me that a steering wheel like the one used by his team cost upwards of US$35,000, almost enough for a nicely equipped BMW sedan. Other highlights include Brembo brakes with phenomenal stopping capability, a 7-speed transmission with a carbon fibre clutch and grippy Michelin racing tires. With the driver in place, but with no fuel in the tank, the BMW F1 car weighs 600 kilograms. Power comes from a “new generation” BMW V-8 with a 90-deg cylinder angle, as required by the regulations, which become harder to figure out as each season goes by and are a maze of

Sponsored Ads

stringent rules and guidelines. The engine displaces just 2.4-litres, but there the comparison with your 4-cylinder road car ends. F1 teams are quite secretive about the performance of their engines and BMW is no exception. However, rpm figures approaching 20,000 are spoken of and power levels can be close to 1,000 hp or even more. The power generated by these engines and the speed at which they have to run is an indication of how much research and development time is devoted to the job. Of course, an organization as wide-ranging as an F1 team doesn’t thrive without very competent management, and at the top of the BMW race effort is Motorsport Director Mario Theissen.

He is the one who has to “get it all together” if the team is to continue the distinguished history of BMW racing. Theissen has been motorsport director since early in 1999 and brings to the role a brilliant engineering background and years of race experience. He joined BMW right after graduating from university in 1977. I spoke to Theissen in the private team area behind the pits at the last Montreal GP and found him very frank, willing to discuss difficult team topics and absolutely determined to take the team to the top. He heads up an extensive workforce based in Munich and is a great believer in “centralized project management.” An ex-marathon runner (he has no time to train nowadays!) he has the skill and

energy to get the job done. So far, the season hasn’t gone too badly for the newly emergent factory team. BMW has scored World Championship points in all but two events in 2006, up to and including Monaco. Expect the BMW team to become a familiar sight at or near the front of F1 grids over the next few years. After all, this is a company that earned its performance reputation the hard way by racing and winning for it. Said Professor Burkhard Goschel, BMW Board Member for Development and Purchasing: “Formula One seems tailor-made for BMW’s brand values and there’s no other sporting event that generates so much attention on a regular basis worldwide. In 2006, we will be primarily building up experience.”