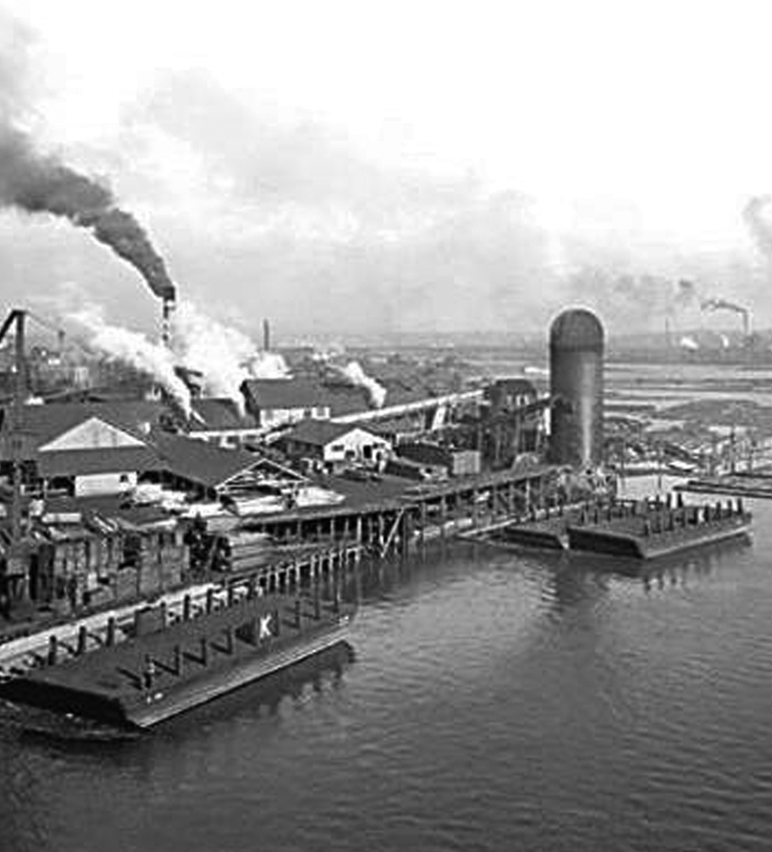

It’s amusing to note, given how dramatically False Creek’s fortunes have shifted over the years, that one of its earliest owners in the 1880s was the Vancouver Improvement Company. That firm was owned by real estate kingpin and future mayor David Oppenheimer, who could not have predicted the “improvements” to come, particularly at the eastern end of False Creek. Originally a saltwater marsh, it was filled in to provide space for two large railway yards during the Second World War. What remained of the creek became Vancouver’s industrial heart, its shores lined with sawmills, coal sheds, metalworks and shipbuilders. By the time the last sawmill shut down in 1983, the opening of the Granville Island Public Market had already spurred nearby residential development on both sides of False Creek.

Expo 86 briefly revitalized the north side and eventually led to a dramatic highrise facelift along Pacific Boulevard. But southeast False Creek, with the exception of that shiny, twinkling, Expo remnant Science World, was never the belle of the ball. Abandoned, rusting barges, crumbling wharves, contaminated soil, acres of empty pavement and chain link fencing: this was not exactly the stuff of an architect’s dreams. Which is why its reinvention as a model, 21st-century residential community—championed by city planners who offered to build a 2010 Winter Olympics athletes’ village on the site—is so intriguing. After 125 years, southeast False Creek is finally getting the extreme makeover it deserves. And the sheer amount of design smarts involved is impressive.

Sponsored Ads

VIA Architects is the project’s urban design consulting firm. As VIA’s Jeff Olson told Shared Vision last year, “This project needs to be the best possible example of sustainable city building that we can make.” It must incorporate the most advanced technology that exists in order to conserve energy, reduce pollution and create a “green” development from rooftop garden to waterfront bicycle path. “Every day I read or hear of some environmental horror story,” Olson pointed out. “And I think you become kind of blind to that because you see it so frequently. It’s obvious that we need to do something to change the way we build cities.” With fully 50 acres of city-owned land awaiting development, almost half of it reserved for parks and green space, adopting eco-friendly methodology represents a huge

change in how that work will be done. For example, instead of undertaking the lengthy, expensive and air-polluting task of removing the contaminated soil by truck (11,000 loads worth), certain areas will be raised in elevation and then sealed under an impermeable plastic membrane and a layer of bentonite clay. Accommodations on the 12-acre athletes’ village site will consist of one- to three-bedroom condominiums, rental units and social housing in low- to mid-rise buildings. All of the buildings will be constructed to meet LEED standards (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), reducing residents’ energy demands by up to 50 percent.

And these are permanent living spaces, unlike the temporary athletes’ villages hastily constructed for previous games in other cities. The spacious digs are much bigger than Olympic requirements dictate and no money will be spent to modify them post-Games. Some facilities will be housed in tents, however; the village plan calls for dining

Sponsored Ads

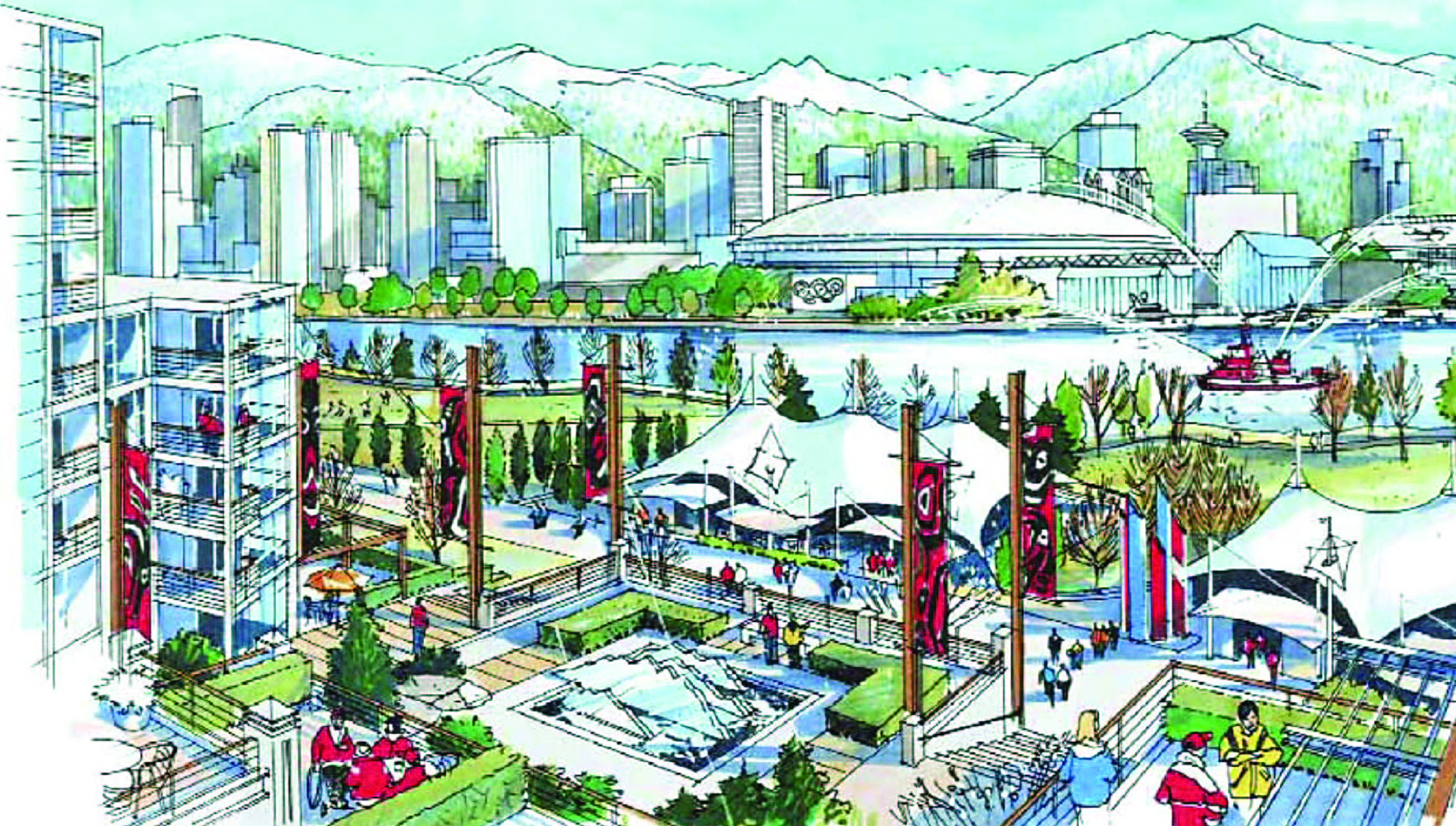

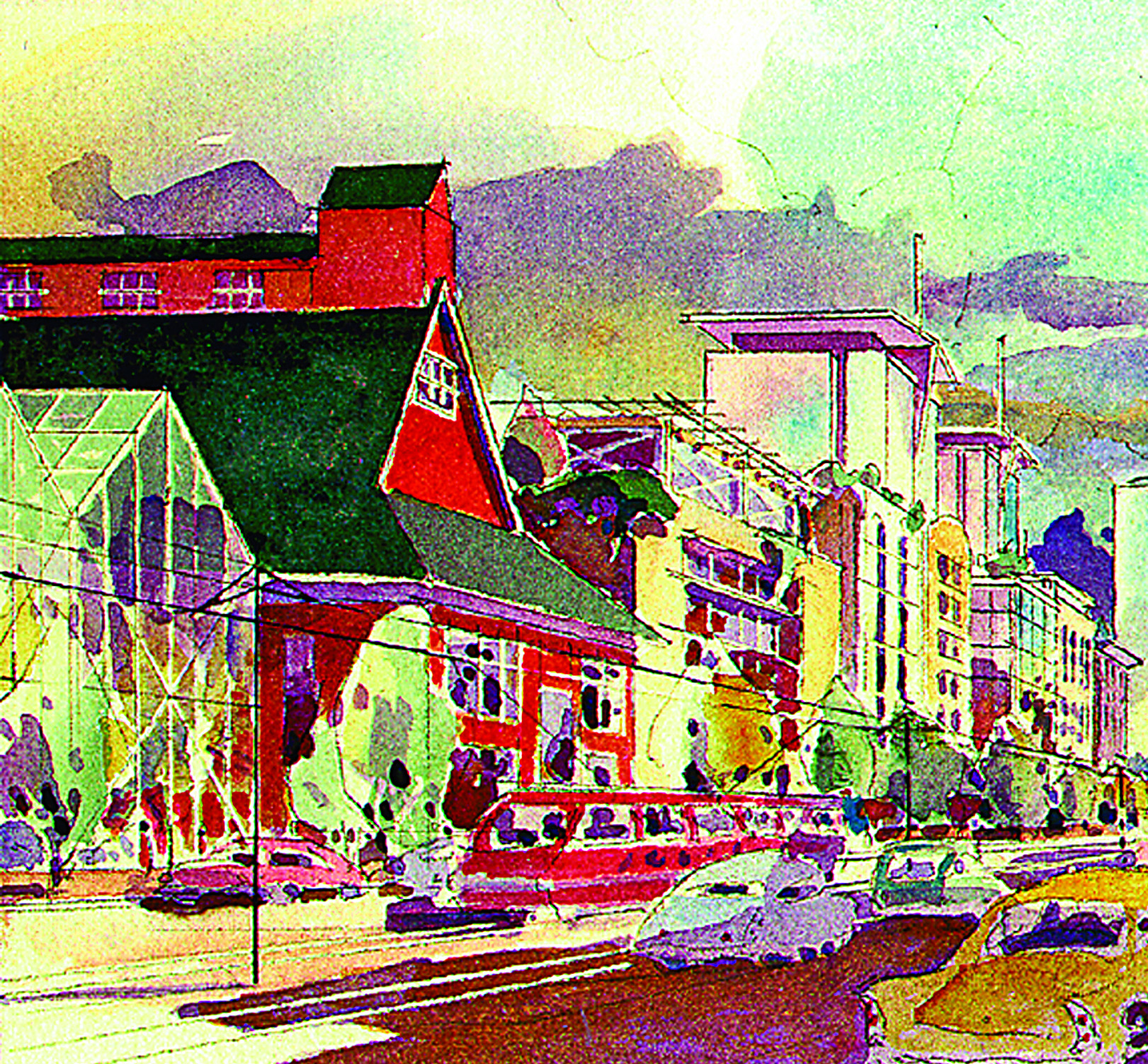

halls, training rooms, a medical clinic, post office and convenience store, most of which are only needed for the duration of the event. But how will southeast False Creek actually look four years down the road? Viewed from offshore on one of the little ferries plying the creek, the transformation will be well underway. Divided into three distinct neighbourhoods tentatively dubbed “Worksyard,” “Shipyard” and “Railyard,” in keeping with the area’s enterprising past, the development has a decidedly small-scale appeal thanks to an abundance of row houses and a 15-storey height limit on other structures. Three waterfront parks will separate the residential areas, connected by a paved, tree-lined Seaside Walkway (bikes welcome). Public art might include First Nations-inspired banners; reflective pools and other water features are also promised. Remediation of the shoreline and the subsequent creation of some wildlife habitat around the creek will encourage birds and other creatures to settle in. The historic Domtar Salt Building, with its friendly red barn exterior and massive wood beams, will be relocated and put to use as a community hall or market—the only heritage structure to be preserved. Narrow, pedestrian-friendly streets with grassy swales will bisect the development. These culvert-like swales will capture stormwater and divert it into various ponds, where it will be naturally “scrubbed” before it empties into False Creek or is reused to irrigate a community garden.

.And there will be plenty of those. The vision for urban agriculture here is far-reaching. UBC landscape architecture grad Alexander Kurnicki wrote his thesis on the topic several years ago, arguing for rooftop vegetable gardens, wild gardens seeded with native berry plants and communal gardens tended by interested residents and fertilized by their own compost. He proposed that mature fruit trees be planted along the right-of-ways and described green houses producing commercial crops for sale. He even suggested an urban farm, complete with grazing pastures for goats and sheep and its own barn (housing livestock and a veterinary clinic), constructed from vintage timbers and steel beams recycled from False Creek’s previous industrial tenants. Kurnicki’s dream is unlikely to become reality. But sections of formerly barren southeast False Creek will certainly be under cultivation by the time the area, including 20 acres held privately, is fully developed. The city anticipates as many as 16,000 people will eventually live here, including families, seniors and low income-earners. Parks, pathways, an extended downtown trolley service and, likely, a bigger fleet of False Creek ferries will make their commutes both convenient and scenic. Residents will live, work and play in one of the greenest urban neighbour hoods in Canada. And conceivably, it’s just what the Vancouver Improvement Company had in mind all along.