Sponsored Ads

Here’s the funny thing about the Olympics, and I don’t mean funny ha-ha: the Games themselves have become huge business, with billion-dollar broadcasting deals and hundreds of millions in funding. But when it comes to actually hosting the Olympics, the business side of the argument doesn’t always make sense.

Yes, the “Olympic Movement” has resurrected itself since its pre-Los Angeles days when it had less than $200,000 in the bank and—despite possessing one of the most recognizable brands on the planet— couldn’t raise the coin to throw its own party. And yes, according VANOC CEO John Furlong, by the time the world’s best winter athletes tweak their first 540s on the half-pipe at Cypress Mountain or curl their first rocks in Queen Elizabeth Park, the organizing committee he has headed up since 2004 will have become “one of the biggest companies in the country,” employing something in the neighbourhood of 4,000 paid employees and 25,000 volunteers.

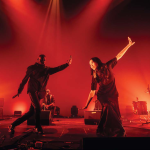

Another 10,000 volunteers will work on the opening and closing ceremonies. So that’s two businesses taken care of, but what about the rest of us? What about the rest of the city? Well, here’s another funny thing about the Olympics: economic impact studies. Bid cities and, later, Olympic host-cities-to-be, toss them around like smiley-faced Nerf balls in an effort to drum up enthusiasm. As Furlong himself told the Vancouver Board of Trade last year, “During the bid days, we talked a lot about economic impact and we placed a lot of numbers out there, and they were heavily debated and argued about.”

The reason for all that argument is that Olympic economic impact studies unfailingly predict stratospheric financial gains stemming from floods of tourists, huge injections of money, unprecedented booms in construction and, generally, the world’s undivided attention. Evidence of those gains after the fact, however, is hard to find. There is always the odd success story, like Vancouver-based Griffin House Screen-printing and Sportswear. Back in 1988 when ski-jumper Eddie The Eagle and the Jamaican bobsled team became surprise heroes of the Calgary Olympics, Griffin House managed to print and ship 5,000 novelty T-shirts per day to Calgary on a 24-hour turnaround.

Obviously construction is booming in Vancouver, and there will be plenty of Olympic-related opportunities for well-positioned restaurateurs, hoteliers, event planners and sports marketers alike. Whether they will enjoy that T-shirt seller’s instant success come 2010 remains a big question. Still, studies of cities that have hosted major sporting events, including the hallowed Olympics, read rather like that old Economics 101 chapter on opportunity costs. They show increased employment in Olympics-related construction balanced by a shortage of construction workers for other jobs.

Investment is equalled or bested by borrowing, and money spent on Games-inspired infrastructure is money not spent on hospitals or education. And then there’s the debt. “Higher, faster, stronger” may be the Olympic motto, but many host cities seem to have embraced the same words as a spending strategy. The first Canadian city ever to host an Olympics is the star of one such cautionary tale. Despite then-mayor Jean Drapeau’s famous avowals to the contrary (“The Montreal Olympics can no more have a deficit than a man can have a baby!”), 30 years after its games, and two years after the Expos took the night train out to play ball in Washington, Montreal is just now making the final payments on Olympic Stadium.

Sydney taxpayers shell out more than $100 million annually for upkeep on their Olympic-built rail system, and Athens recently revealed its annual upkeep costs of $128.8 million. On the face of it, the questionable financial promise of hosting the Olympics is not the sort of thing local business owners and government finance ministers tend to embrace. Why, then, are ours so bullish on 2010? And why have some of the most famous cities in the world, cities like New York, London, Madrid, Paris, Salzburg and Moscow, also been clamouring for the opportunity to spend billions of dollars to host the world’s biggest sporting event? Funny Thing About The Olympics Number Three: It’s not always about the bottom line.

Sometimes it’s about the power, and not the evil, world domination kind either. The great power of the Olympics for Vancouver is in the opportunities it presents. No matter the cost, every city needs to generate urban renewal, to improve infrastructure and to support its arts and culture if it is going to remain healthy and viable. Vancouver and area has the unique opportunity to use the public money and political attention that comes from hosting the Olympics as its fast track to all of those things. For a city and province so

Sponsored Ads

long and notably removed from the economic and political centres of the country, this is pretty exciting stuff. For better or worse, B.C. is now a province the Prime Minister comes to visit. He’s not even here to ask for votes, at least not directly. He’s here to spend money, $55 million of it most recently to match Gordon Campbell’s $55 million final, final injection into VANOC’s burgeoning venue construction budget. It’s taxpayers’ money to be sure, but it’s nice to be noticed. Besides, $55 million is nothing to British Columbians, it’s barely a bowsprit in a fast ferry fleet. This is the Winter Olympics, after all. They are half as big as their summer counterpart and cost half as much. Done right, however, their long-term value can be great. While Montreal wallowed in its Summer Olympic-sized debt for three decades, Calgary turned an estimated $150-million profit on its 1988 Winter Games and has never looked back. Not only did the city grow in international stature

from a town with some horses and a bar to, well, a town with some horses, more bars and a whole lot of money, but its new, world-class training facilities became the gravitational centre of every elite Canadian winter athlete’s universe. By the time the Olympic flame ignited the cauldron in Salt Lake City in 2002, a disproportionate 85 of the 156 Canadians who competed there were natives of Alberta or had trained in and around Calgary for at least a year. That’s just the sort of business VANOC was hoping to drum up when it asked for that $110-million infusion for construction. According to Vancouver 2010 Chairman of the Board Jack Poole, the extra cash is “excellent news for Canadian athletes dreaming of winning gold in 2010, as we can now confidently work towards providing them with the opportunity to train on Vancouver 2010 venues well before the Games.” If those facilities attract athletes the way Calgary’s have, that extra cash will prove to have been excellent news too for local businesses that will feed, clothe, house and train all of those new citizens long before the Games begin. Of course the sun will still rise every morning over the thickening skies of the Fraser Valley whether we build a luge track in this province or not. But if Vancouver is going to evolve into one of the world’s great cities, something it’s been poised to do since its last big evolutionary spurt inspired by

Expo 86, it needs an expanded trade and exhibition centre, it needs more and better public transit and it needs a direct link from the airport to downtown. Like them or not, these are the projects that make cities better, better for business, better to visit and better to live in. Each would have been completed eventually, but nothing focuses the capital flow or expedites a timeline like the fast-approaching opening ceremonies of the Olympic Games. In Vancouver/Whistler’s case, those opening ceremonies in BC Place stadium will start the flow of nearly 7,000 Olympic and Paralympic athletes and officials and another 10,000 media types. The question is, what kind of city will they see? If organizers stay the course, they’ll see the birth of a new and promising neighbourhood in Southeast False Creek, where prime land left fallow for the last two decades has the potential to set a new standard for urban sustainability. On paper, the innovative Athletes Village planned for the site will be converted into a mix of market and non-market housing after the Games. In other words, if it’s done right, worldwide television viewers and visitors alike will see a city use the power of the Olympics to build affordable housing where it is very sorely needed. And they’ll see a city and a province with a healthy heart. Local cultural, community and recreation centres are already being refurbished. Some communities will get new, non-Olympic facilities. Public

spaces, like grand old Hastings Park, will receive much needed attention. Through the provincially funded and somewhat nebulously commissioned 2010 Legacies Now programs, time and resources are being invested into volunteerism in the province, into local sport and recreation, into literacy and into art. A funny thing is about to happen on the way to the Olympics. A 17-day sporting event with 3,000-year-old roots is going to give a still wet-behind-the ears city the uncommon chance to reinvent itself. According to John Furlong, making the most of that chance “is about getting everybody to look at the Games and remind themselves that the world is coming and that we all need to be at our best.” That may not sound like much of a business plan, but there’s a reason economics is called the dismal science. There are some things fiscal reports simply won’t show. Informed, cultured, literate citizens thriving in a revitalized city are a few of them. It’s a funny thing how you just can’t measure the good life.